Biblical Geography: Why Christians Should Study It

By: Guest Writer Chris McKinny, Director of Research, Gesher Media

Why should Christians study biblical geography? Two reasons.

First, the majority of the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament are historical narratives that are rooted in distinct and temporal geographical contexts with specific cultural and spiritual dimensions. Therefore, you should study biblical geography because your understanding of Scripture will be incomplete, less interesting, and lacking in context without a thorough grounding in the real-world of ancient Israel and Second Temple Judea.

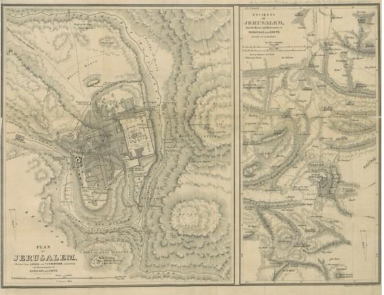

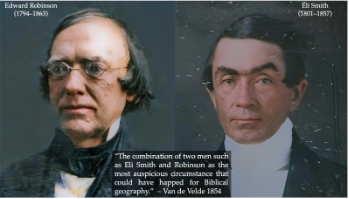

Second—and you may not realize this—but our ability to reconstruct the landscapes of Scripture is very new! Christians and Jews have always been interested in the “Holy Land” and the “Holy Places,” but it was not until the early 1800s that the political conditions in Ottoman Palestine allowed for the extraordinary and rapid re-discovery of ancient biblical regions and places. While there are many explorers and pioneers during this period, one exploration stands out above the rest—the 1838 expedition to the Holy Land by Edward Robinson (1794–1863) and Eli Smith (1801–1857) that resulted in their seminal work, Biblical Research in Palestine (1841).

Edward Robinson was one of the most significant biblical scholars to have ever lived and the father of biblical geography. Eli Smith was an American protestant missionary and brilliant Arabicist—his Arabic translation of the Bible remains one of the most widely used. Together, they unlocked the secret to biblical geography: the memory of biblical place names (toponymy) in the Arabic language of Ottoman Palestine. Some places, like Jerusalem and Jaffa, were never lost. But many, many others were lost to history.

For example, Robinson identified the ancient city of Jezreel (where Jezebel was killed; see 2 Kings 9:30–37) by closely reading a vast array of historical sources and noticing that the Arabic name of the village of Zerʿin was quite close to the Hebrew Yizrꜥeʾl. By practicing (and inventing!) the discipline of historical geography, Robinson is credited with correctly identifying hundreds of biblical places that set the stage for future exploration in biblical geography and laid the foundation for biblical archaeology in the latter part of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

While we would be wise to not practice “chronological snobbery,” there can be no question that modern students of the Bible are privileged over their predecessors in that they have access to the real geographical and cultural (i.e., archaeology) settings of the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament. In fact, we not only have an immense amount of information about the biblical world, but we also actually have some contemporary graphic maps!

Near-Contemporary Graphic Maps

We would love to have graphic maps originating from ancient Israel or Second Temple Judea, but no such Israelite or Judean maps have survived. Despite our lack of biblical graphic maps, we do have some near-contemporary maps that give us a lot of interesting information about how Israel’s neighbors viewed and portrayed the world.

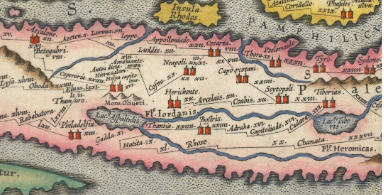

One of the oldest graphic maps ever found comes from the region of Babylon, and it may even point to the location of where ancient Mesopotamians believed Mount Ararat and its fabled ark was located (see Genesis 8:4)! For the New Testament era, the Peutinger Map is a medieval copy of a Roman-era traveler’s map that likely originated in the second or, even, first century CE. Among many other interesting details—we can see the route with distances from Beth-shean (Scytopoli) to Jericho (Herichonte)—a route that Jesus and the disciples would have regularly used such as when they were “passing along between Samaria and Galilee” (Luke 17:11 – all translations, ESV). This map was even used in the Capernaum set of “The Chosen.”

The Real Bible has Maps at the Beginning, not at the End

In terms of the Bible itself, we have the next best thing to graphic maps: authentic spatial information that is reflective of the real-life settings of the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament. Modern printed English Bibles include maps at the very end, but both the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament feature maps near the beginning. You might be wondering, where are these biblical maps? These are not graphic maps, but textual maps made up of geographical descriptions and lists of place names (toponyms) arranged with geographical consistency.

Genesis 10: The Hebrew (Textual) Map of the World

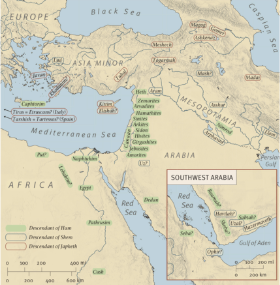

Genesis 10, the so-called “Table of Nations,” is a map of the wide world of the Hebrew Bible. At the far extremes this includes Tarshish (Sardinia and/or southern Spain) and Put (Libya) in the west (Genesis 10:4, 6), Ophir and Sheba (Yemen and Ethiopia) in the south (Genesis 10:29), and Assyria (Iraq) and Elam (Iran) in the northeast (Genesis 10:22). The story of Jonah involves the two furthest points in the west and east: “‘Arise, go to Nineveh (i.e., one of the main cities of Assyria), that great city, and call out against it, for their evil has come up before me.’ But Jonah rose to flee to Tarshish from the presence of the LORD” (Jonah 1:2–3). King Solomon’s fame and wisdom are so far-flung that it even reached the ears of the “queen of Sheba” who “came to test him with hard questions” (1 Kings 10:1).

Of course, the interior of the map is just as important with the peoples of the Land of Canaan described as the Hittites (around Hebron), the Jebusites (Jerusalem), the Hivites (north of Jerusalem) (Genesis 10:15–16)—peoples that Abraham encountered (Genesis 15:19–21) and his descendants would later drive out (Joshua 3:10). Reading Genesis 10 as a map for the unfolding story of the Hebrew Bible allows one to visualize the geographical settings of Scripture from the age of the patriarchs through the exile and beyond.

Scripture “Shows” Biblical Geography

This type of thinking also helps us understand the significance of such sections of Scripture that seem less important, such as Joshua 12–21. These chapters are not only important for showing Israel’s tribal inheritance in the Land of Canaan, they are also distinct maps of Israel’s conquest (Joshua 12) and settlement (Joshua 13–21) that allow us to assess and understand the historical geographical settings of early Israel.

Significantly, the textual map of Israel served as the backdrop for not only the story of the Hebrew Bible but also the sacred landscape of the life and ministry of Jesus. The Synoptic Gospels, in particular, present Jesus’ ministry as a kind of territorial and conquest, beginning with his baptism at the Jordan River (like Joshua and Elisha), his temptation in the wilderness (like Moses and Elijah), his defeat of the demonic forces of Israelite Galilee (like Joshua), and his royal approach to Jerusalem (like David) to defeat Satan and death (like only Him). With the Lord’s Table, Christians continue to commemorate Christ’s conquests in Jerusalem on Passover, but that was not the end of the story.

Acts 2 – The Crowds at Pentecost, Textual Map for the New Testament

Acts 2 is mostly known for the amazing event of the Holy Spirit inhabiting the Jewish people gathered to celebrate Pentecost/Shavuot. I have written on some fascinating aspects of this extraordinary event here and here. In short, it was a great plot-twist. After the Spirit’s departure in the days of Ezekiel (Ezekiel 8–11), Jews had long-awaited God’s Spirit to return the Jerusalem Temple. It did just that on Pentecost, but this time God’s Spirit unexpectedly went into living, breathing temples (1 Corinthians 3:16–17). While there are many layers of significance to the Spirit’s descent on Pentecost, one of the oft-missed details is biblical geographical details embedded in the story. Let’s take a quick look at the passage:

Now there were dwelling in Jerusalem Jews, devout men from every nation under heaven. And at this sound the multitude came together, and they were bewildered, because each one was hearing them speak in his own language. And they were amazed and astonished, saying, “Are not all these who are speaking Galileans? And how is it that we hear, each of us in his own native language? Parthians and Medes and Elamites and residents of Mesopotamia, Judea and Cappadocia, Pontus and Asia, Phrygia and Pamphylia, Egypt and the parts of Libya belonging to Cyrene, and visitors from Rome, both Jews and proselytes, Cretans and Arabians—we hear them telling in our own tongues the mighty works of God.” And all were amazed and perplexed, saying to one another, “What does this mean?” (Acts 2:5–12)

No less than 15 geographical regions are included in this description! On one level this shows the breadth of the Jewish diaspora in the first century CE. On another level, it is quite clear that Luke included these details as a textual map at the beginning of his account for the unfolding story: “all that Jesus began to do and teach” (Acts 1:1). Indeed, Jesus himself gave the outline and purpose of the book of Acts as follows: “You will receive power when the Holy Spirit has come upon you, and you will be my witnesses in Jerusalem and in all Judea and Samaria, and to the end of the earth” (Acts 1:8).

Like Genesis 10, we are given a glimpse of the wide-world, now (mostly) under Roman imperial control, in which the first churches will be founded and grow. In this sense, Acts 2:5–12 functions as a textual map for the rest of the book of Acts—especially Paul’s missionary journeys to Asia Minor and Greece—as well as geographical landscape for the rest of the New Testament. We can also see the close relationship between Genesis 10 and Acts 2. God’s promise to Abraham was that “in you all the families of the earth shall be blessed” (Genesis 12:3), and Peter proclaimed the fulfillment of that promise beginning in Jerusalem with the resurrection of Jesus (Acts 3:25). In this sense, Acts 2 may be read as both a Pentecost Map and an itinerary of Christ’s intended conquests—a conquest that Jesus led and directed from the right hand of the father, appearing and guiding his servants to the right locations and situations (for example, Paul in Corinth in Acts 18:9–10). That conquest certainly had a westward trajectory.

Northeast

In the northeast, Media, Parthia, Elam, and Mesopotamia (the latter being a reference to the entire region of Iraq, but usually its northwestern section, cf. Acts 7:2) were heavily populated by Jews taken there during the 586 BCE Babylonian exile (2 Kings 25), and perhaps also Israelites exiled even earlier by the Assyrians in 722 BCE (2 Kings 17). During the first century, this region was part of the Parthian Empire, Rome’s great eastern rival. While there are no accounts in the New Testament of missionary activity in the east, it is clear from history and archaeology that Christianity did spread there, including to Armenia, one of the most ancient Christian communities. Indeed, there was a very large Iraqi Jewish presence from antiquity until 1948 and the founding of the State of Israel when Jewish populations residing in Arab countries were forcibly driven from their homes. Interestingly, the epistle of Jacob (we call him “James,” but his real name was Jacob) is addressed to the “twelve tribes in the Diaspora” (James 1:1), which certainly included Jews and Christian converts living in the Parthian Empire.

South and Southwest

The south and southwest points of the Pentecost Map are the regions of Libya, Cyrene, Egypt, and Arabia (a name that also includes the region of Mount Sinai). In each of these, there were sizable Jewish populations in the diaspora. Of course, Simon of Cyrene (Luke 23:26) carried Christ’s cross to Golgotha, but we also know that Cyrenians, as well as Alexandrians (from Lower Egypt), were present in Jerusalem at the synagogue of the Freedman (Acts 6:9). Converted Jewish Cyrenians, along with “men of Cyprus,” helped spread the message to Antioch (Acts 11:19–21; see also Lucius of Cyrene, teacher/prophet of Antioch, in Acts 13:1).

Of course, Alexandria, was the second-largest Roman city and a major center of Jewish life and thinking (e.g., Philo of Alexandria – c. 20 BCE–50 CE). Apollos was one such bright Jewish Alexandrian who was baptized by John the Baptist and became a powerful proclaimer of the gospel in Ephesus in Corinth (Acts 18:24–28). Paul’s final journey in Acts includes traveling on ships “of Alexandria” (Acts 27:6; 28:11).

After the Lord appeared to Paul on the road to Damascus, Paul “went away into Arabia” (Galatians 1:17), likely referring to Mount Sinai (i.e., Jebel Musa, cf. Galatians 4:25), where he—like Moses and Elijah before him—received revelation from the Lord.

While Ethiopia (biblical Cush), the far southern reaches of the known world, does not appear in the Pentecost Map, Philip’s meeting with an “Ethiopian, a eunuch, a court official of Candace (Queen Candace Amanitore, c. 1 BCE–50 CE), queen of the Ethiopians” led to the eunuch’s conversion, and we can assume the conversion of many to Christ. As an aside, the Ethiopian Jewish background (assumed by the eunuch “reading the prophet Isaiah”) remains shrouded in mystery. But an exciting new project is seeking to shed new light on early worshippers of the God of Israel in Ethiopia!

Western Points

The western points of the Pentecost Map, Cappadocia, Pontus, Asia, Phrygia, and Pamphylia—anticipate a shifting center of the Christian movement from its Judean base in Jerusalem to Antioch to Asia Minor and Greece. Clearly, Paul’s missionary journeys were directed at spreading the gospel through its proclamation at Jewish synagogues throughout the eastern Roman Empire. This overarching strategy clearly worked with major churches emerging especially at Ephesus (the major city of Asia) and Corinth (the major city of Greece). While we have a lot less information about his missionary career, Peter’s first epistle was addressed to “the diaspora in Pontus, Galatia, Cappadocia, Asia, and Bithynia” (1 Peter 1:1)—the same regions in Asia Minor (modern Türkiye) given in the Pentecost Map.

Rome

But of all these geographical conquests of Christ, the greatest was the one near the end of Pentecost’s map: Rome (Acts 2:10). Although Paul did not visit Rome during his missionary journeys, it is clear that the Christian movement had already been established following Pentecost, as we know that Priscilla and Aquila were from Rome (Acts 18:1–4). Of course, Paul wrote the most important letter ever penned to this church long before he came to the city (Romans 1:10). We don’t know if Paul ever made it to Roman Spain (Romans 15:24, 28)—the pre-Colombian western “ends of the earth”—but we do know he made it to Rome.

Luke’s account of the story of Jesus began with the birth of a child born on the far eastern reaches of Caesar’s empire. Luke’s story concludes (but does not end) with Jesus directing His most impactful servant to Caesar’s audience in Rome (Acts 27:23–24; 28:19). Christ’s territorial conquest continued long after Nero removed Paul’s head ensuring that “all the families of the earth” would be blessed through the seed of Abraham.

Why Study Biblical Geography?

In light of the above, I will conclude with the following piece of advice: anyone who is interested in serious studying the Bible should seriously study biblical geography!

Related Articles

The Gospel Spreads from Caesarea to Rome

Outpouring of the Holy Spirit in Caesarea

Keep Learning

The Feasts of the Lord and Their Rich, Biblical Significance

Below, the author has put together a few resources related to the study of biblical geography with a brief description:

- Biblical geography plays a major role in our investigation of Legends of the Lost Ark—Gesher Media’s soon-to-be released documentary feature.

- Regions on the Run from BiblicalBackgrounds – this is the go-to curriculum for reading the Land. Generations of students of biblical geography (myself included) have used Biblical Backgrounds materials to develop their knowledge of biblical geography.

- Holman Illustrated Guide to Biblical Geography: Reading the Land by Paul Wright – this is the go-to textbook for studying biblical geography that is written in the tradition of great predecessors (George Adam Smith’s The Historical Geography of the Holy Land and Denis Baly’s The Geography of the Bible). For 25 years, Wright lived and taught biblical geography in Jerusalem at Jerusalem University College (myself included).

- Photo Companion to the Bible from BiblePlaces.com – this is an excellent resource for learning and teaching biblical geography. I had the immense privilege of working on most of the Hebrew Bible volumes in the Photo Companion to the Bible. Todd Bolen’s excellent blog – BiblePlaces blog is also a go-to resource for staying up-to-date on all things related to biblical archaeology. For three decades, Todd has continued to faithfully teach biblical geography exposing generations of students to its wonders (myself included).

- Biblical World Podcast – As part of the OnScript podcast network, the Biblical World podcast engages with all manner of archaeological, geographical, and cultural studies and discoveries connected with the Biblical World (disclaimer alert: I am one of the co-hosts of the podcast). See especially this episode on Biblical Geography with John Monson, as well this episode on our favorite aspects of Biblical Geography.

- ESV Archaeological Study Bible – I love the ESV Archaeological Study Bible. Of course, it includes numerous helpful notes and essays about biblical archaeology, ancient culture, and biblical geography from experts in the field. But my favorite part about it is that it also includes all of the maps from the ESV Bible Atlas in-line with the text. Thus, if you are reading Acts 2 you will find a map illustrating the locations mentioned in Acts 2:5–12. I also highly recommend getting the ESV Archaeological Study Bible from Accordance Bible Software, which is the most important resource for biblical study.

- Land of the Messiah Map from Gesher Media – this map includes illustrations of all of the major events of the Gospels with two inset maps of the Sea of Galilee and Jerusalem; it also comes with over two hours of teaching (video) related Jesus and geography (by yours truly).

- The Odyssey of Marcus Panthera by Makram Mesherky – ever wondered what it would be like to travel around the Land of Israel during Jesus’ ministry – if so – this book is for you!

- Go to the Land! – The best way to study biblical geography is to see it for yourself and go to the Land! I highly recommend studying with Jerusalem University College either on a short-term tour or as a student living on their Jerusalem campus. I have had the great pleasure of studying (and now teaching) biblical geography at JUC. For more information – you can reach out to me here.